Egyptian Revival

1880-1930

The Egyptian Revival style is one of the styles that permeated all aspects of the arts, from the decorative arts to architecture. The American fascination with Egyptian culture dates back more than 150 years, and stylistic elements from the far-away land have appeared numerous times in fits and starts in American art and architecture since the early1800s. Many Americans knew Egypt through the texts of the old testament. The imagery of Moses winning freedom from the Pharaoh struck a chord as a parallel to the American Revolution, and the association with funerary monuments made Egyptian forms doubly appropriate for cemeteries. The extraordinary longevity and timeless quality of Egyptian art made it appealing for memorials, especially since it seemed to have a hidden meaning.

The allure of Egypt first appeared in the United States in the 1820s following the translation of the Rosetta Stone, which after 20+ years of study, unlocked the secrets of hieroglyphics. From this discovery came a surge of public interest of all things Egyptian as the style was used to enliven gardens, cemeteries and architectural ensembles of that very formal age. Reaching its peak in the 1830, the Egyptian style began a slow fade in the 1850s. Then another resurgence came during the Victorian era of the 1880s following the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869.

The Egyptian Revival that most Washingtonians are familiar with dates from the early 20th century. After the discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922, ancient Egyptian-inspired architectural forms recaptured the imagination of Europeans and Americans alike again and led to a third revival. During this revival, Sphinxes, pyramids, obelisks, and temples hinted at the age of secrets, which were suddenly accessible to a newly enlightened world.

The public devoured every crumb of information as King Tut’s tomb was painstakingly explored by British Egyptoplist Howard Carter and his colleagues. The media was eager to fill the desire for information. Motion picture news-reels, magazines, and newspapers all featured the latest developments of the excavation. Two years after the discovery, in 1924 the New York Times Pictorial Magazine carried the first color photos shown in the United States of the treasures from Tut’s tomb. Articles about Tutankamun carried well into the 1930s as archaeologists took ten years to completely clear the tomb. During that time the public’s taste for the exotic was meet with additional stories of ancient Egyptian life of a more general nature.

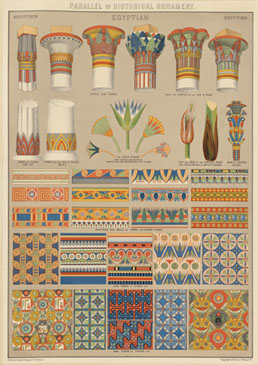

On the scholarly side, several detailed studies of the architecture of ancient Egypt appeared which allowed architects to mimic the details and intricate symbology of the newly rediscovered. Perhaps the earliest scholarly description of ancient Egyptian structures in America appeared in the March 1829 issue of the American Quarterly Review where they devoted forty pages of one issue to Egyptian architecture. The first complete book on architectural history published in the United States in 1844 also featured a chapter on Egyptian architecture. Later studies such as Ancient Egyptian Masonry, the Building Craft by architect and Egyptologist George Somers Clarke & engineer Reginald Engelbach published in 1930, gave architects specific measurements and design motifs to use.

The architectural style is based loosely on Egyptian architecture from the third millennium B.C. to the Roman Period. Rarely were entire buildings built in the style. Instead Egyptian elements were added to buildings designed in whatever popular style prevailed at the time. Sometimes decorative elements were incorporated into theme rooms, and/or furnishings.

The architectural style is based loosely on Egyptian architecture from the third millennium B.C. to the Roman Period. Rarely were entire buildings built in the style. Instead Egyptian elements were added to buildings designed in whatever popular style prevailed at the time. Sometimes decorative elements were incorporated into theme rooms, and/or furnishings.

Egyptian architectural motifs include bulging columns with lotus leaf columns, which sometimes resembles stalks tied together with horizontal bands below the capitals. Cavetto (curved) style cornices and statuary of Egyptian rulers can also be found. Walls were constructed of brick and/or stone masonry or were covered with stucco or terra-cotta tiles to imitate some form of masonry construction. Many walls are battered, sloping outward as they approached their foundation. Window and door architraves that slope sharply inward as they rose foretell of stone foundations that supposedly carried the imaginable weight of monumental walls. Winged orbs (Scarab beetles) above windows and doors and on cornices, pylons, obelisks and hieroglyphics markings were all symbols that could bring the wisdom of the east to the naive western society.

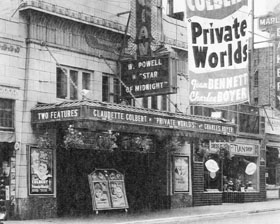

Egyptian revival never became widespread and examples in Washington State are rare. It was rarely used in residential applications. For the average homebuyer it seems that reading about King Tut or going to an Egyptian movie house could be exciting, but to actually invest in building an Egyptian style dwelling was more than they were willing to do. Instead the style was applied to theaters, exhibit buildings and fraternal halls on a selective basis. In fact, the style was the adopted imagery of the Freemasons, thus many lodge buildings have Egyptian Revival motifs. More common was the use of the style in funerary applications. In many people minds, ancient Egypt was associated with tombs and eternity. It was therefore only natural that Egyptian design would frequently be used in cemeteries. The cemetery, enclosed with an Egyptian-style gate, or a tombstone with a curved/Cavetto style cornice, could read as a metaphor for the soul attaining freedom from earthly bondage. The Egyptian obelisk became synonymous symbol of remembrance and the afterlife.

While some decorative elements show up in the decorative arts movement of the Art Deco period, the popularity of the Egyptian style began to wane with the introduction of streamlined modern design in the 1930s and is altogether gone from the mainstream architectural vocabulary by 1935.

Washington State Examples

|

|

|

| Lawrence Daniel House Tacoma - 1928 |

Masonic Temple Yakima - 1911 |

Anderson Monument - Lakeview Cemetery Seattle - c.1928 |

|

|

|

| Rucker Monument - Evergreen Cemetery Everett - 1907 |

Obrien - Porter Monument - Fairmount Cemetery Spokane - 1925 |

Masonic Hall Bellingham - 1892 |

|

|

|

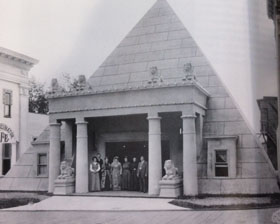

| Temple of Palmistry - AYP Expo Seattle - 1909 |

Masonic Temple Spokane - 1915 |

Egyptian Theater Seattle - 1928 |

For More Information:

- Curl, James Stevens Egyptomania: The Egyptian Revival, a Recurring Theme in the History of Taste Manchester University Press, London, 1994.

- Carrott, Richard G. The Egyptian Revival: Its Sources, Monuments and Meaning. University of California Press, Berkey. 1978.

- “Three Egyptian Revivals” Old House Interiors, Jan 2002.

- Clarke, Somers & Reginald Engelbach. Ancient Egyptian Masonry: The Building Craft. Oxford University Press, Milford, UK, 1930.

- Petrie, W.M. Flinders The Arts & Crafts of Ancient Egypt. T.N. Foulis, London, 1910.

- “New Tacoma Homes are Varied Types” – Tacoma Sunday Ledger. June 3, 1928. pg A4

- "Riddle of the Sphinx Solved at Last" - Seattle Times: June 16, 1929.

- Baker, John M. American House Styles: A Concise Guide. W.W. Norton & Co., New York, N.Y. 1994.

- Carley, Rachel, The Visual Dictionary of American Domestic Architecture, A Roundtable Press Book, New York, NY. 1994

- Massey, James & Shirley Maxwell, House Styles in American: The Old-House Journal Guide to the Architecture of American Homes Penguin Books, New York, NY, 1996

- McAlester, Virginia & Lee, A Field Guide to American Houses Alfred A. Knopf, New York, NY, 1992.

- Walker, Lester, American Homes: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of Domestic Architecture, The Overlook Press, New York, NY 1981.

- Howe, Jeffery, Houses of Worship: An Identification Guide to the History and Styles of American Religious Architecture, Thunder Bay Press, San Diego, CA, 2003.

- Whiffen, Marcus. American Architecture Since 1780. MIT Press, Massachusetts. 1969.