Stick Style

1870-1895

The Stick style was a late 19th-century American architectural style, and is considered by many as a transitional style found between the Carpenter Gothic style of the mid 19th-century, and the Queen Anne style that it had evolved into by the 1890s. It is named after its use of linear "stickwork" (overlay board strips) on the outside walls which mimic an exposed half-timbered frame. The style represented the most innovative design concepts and building technologies of its time, yet it did not attract serious study—or even a widely accepted name—until a century later. Were it not overshadowed by the equally extroverted Italianate, Second Empire, and Queen Anne styles by the 1880s, and through much of the 20th century, it’s clear that the Stick style would have been recognized much earlier for its original identity and the totally American concept that it presented for the first time.

The Stick style was a late 19th-century American architectural style, and is considered by many as a transitional style found between the Carpenter Gothic style of the mid 19th-century, and the Queen Anne style that it had evolved into by the 1890s. It is named after its use of linear "stickwork" (overlay board strips) on the outside walls which mimic an exposed half-timbered frame. The style represented the most innovative design concepts and building technologies of its time, yet it did not attract serious study—or even a widely accepted name—until a century later. Were it not overshadowed by the equally extroverted Italianate, Second Empire, and Queen Anne styles by the 1880s, and through much of the 20th century, it’s clear that the Stick style would have been recognized much earlier for its original identity and the totally American concept that it presented for the first time.

While such a perspective is academically accurate generations later, in its day the Stick style was nothing if not totally fresh, up-to-date and, most of all, modern. While some critics found the style slightly vulgar, few could deny the style was inventive and vivacious. People of wealth and standing, wanted buildings designed in the style. The style is found mainly on dwellings but can be found on other building types. Most were probably architect-designed, and the brightest talents in the newly prominent architectural profession were attracted to the style.

What propagated the Stick style at the popular level, however, was most likely the flood of new house-building plan books that appeared after 1850. Architect-publishers like Gervase Wheeler and Henry Cleaveland flashed the Stick look far and wide in their books Rural Homes (1851) and Village and Farm Cottages (1856) as part of a broad menu of building designs. These plan books and others inspired local builders to erect Stick styles houses, and/or incorporate their details, on a truly national scale for the first time.

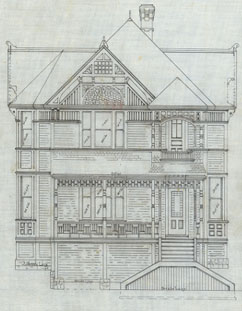

Ultimately, Stick style buildings are about carpentry - the latest advances in wood technology from a country that had lots to offer. Unlike the chunky, ground-hugging Gothic and Greek Revival styles that emulated the massing of masonry even when built of wood, Stick style buildings are generally light and irregular in feel; a freedom of form made possible by the new system of balloon frame construction with milled 2” x 4” lumber and nails. Rather than dividing the space within a simple rectangular or cross-shaped plan into rooms and halls, Stick style buildings often pushed the space beyond the footprint; so much so you can sometimes read the interior space from outside the building.

Like the Queen Annes to come, Stick style buildings generally exhibit a strong vertical emphasis, with tall windows, multiple stories, and surface ornament reaching skyward along with sharply pitched roofs and monumental towers. More than Queen Annes, however, Stick style buildings are angular. Roof plans are complex, often with intersecting gables and roof effects, such as clips, hoods, and kicked eaves / bonnet roofs. Window bays and towers are generally squarish, with roofs that are pyramids or similar polygons. Other characteristics include wrap-around porches, upside down picket-fence patterns, spindle detailing, and radiating spindle details in gable peaks. Windows are usually large one-over-one or two-over-two and, frequently paired, fit within the patterns created by stick work.

The defining feature of these buildings, however, is stickwork: expressive wood facing and ornament that evokes the grids and angles of structural framing in their layout. In Stick buildings, the exterior clapboards and shingles are divided into panels by vertical and horizontal boards, bringing the symbolism, if not the actual position, of the underlying posts and joists to the façade. Note that the stickwork decoration is not structurally significant, rather they are narrow planks or thin projections applied over the wall's clapboards.

Diagonals are common, enhancing the structural feel with a hint of the medieval. Often the beaded siding found within rectangular panels is also laid diagonally and mirror imaged in an adjacent panel. More diagonals pop up as pseudo-structural brackets supporting roof eaves or trusses spanning gable ends—woodwork that was easy to mass-produce with new steam-powered machinery. Curves are rare except for the periodic semicircular porch bracket or window top.

Highly stylized and decorative versions of the Stick style are sometimes referred to as Eastlake. English architect and tastemaker Charles Locke Eastlake initially spoke about reforming the design of English furniture and furnishings, but by the time his widely read columns and book, Hints on Household Taste (1868, which went into six editions), had filtered across the Atlantic, they found traction not with the furniture industry, but the house-building public. His call for furniture ornament that was simple, finely crafted, and closely related to the structure of the object, materialized as exterior building millwork that was aggressively turned, sawn, and carved. The Stick style was the first architectural style to take this millwork to heart with incised verge boards, fret-sawn railings, and porches ringed with spindles. By the 1880’s publications such as Scientific America were calling house designs “Eastlake”, and some product manufactures used the enduring term to market their wares.

The Stick-Eastlake style enjoyed modest popularity in the late 19th century, but there are relatively few surviving examples of the style when compared to other more popular styles of Victorian architecture. While the style began in the 1850s, like many other styles, here in the Pacific Northwest it fell out of fashion much later than in other parts of the county; with surviving examples found built into the mid-1880s.

WA State Examples

|

|

|

| Gatches Mansion, LaConner - 1891 |

OR & N Depot, Dayton - 1881 |

House, Bellingham - c.1880 |

|

|

|

| Chares Newell House, Goldendale - 1890 |

Henry Drum House, Tacoma - c.1888 |

House, Tacoma - c.1885 |

|

|

|

| House, Mount Vernon - c.1890 |

Lombard House, Bainbridge Island - 1865 |

House, |

For More Information

- Waldhorn, Judith L. A Gift to the Street. Antelope Island Press. San Francisco, CA, 1976.

- Pomada, Elizabeth & Michael Larsen. Daughters of Painted Ladies. E.P. Dutton. New York, 1987

- Bock, Gordon "The Stick Style" Old House Journal, May/June 2003.

- Baker, John M. American House Styles: A Concise Guide. W.W. Norton & Co., New York, N.Y. 1994.

- Carley, Rachel, The Visual Dictionary of American Domestic Architecture, A Roundtable Press Book, New York, NY. 1994.

- Massey, James & Shirley Maxwell, House Styles in American: The Old-House Journal Guide to the Architecture of American Homes Penguin Books, New York, NY, 1996.

- McAlester, Virginia & Lee, A Field Guide to American Houses Alfred A. Knopf, New York, NY, 1992.

- Walker, Lester, American Homes: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of Domestic Architecture, The Overlook Press, New York, NY 1981.

- Whiffen, Marcus. American Architecture Since 1780. MIT Press, Massachusetts. 1969.